Rachel and I recently saw A Complete Unknown (2024), a biographical musical delving into Bob Dylan’s early life in the 1960s Greenwich Village folk scene.

The film unfolds the story of 19-year-old Dylan, who left Minnesota to pursue music in New York, where he emerges as a key figure in the folk revival. It explores his connections with folk icons Woody Guthrie and Pete Seeger, along with his romantic relationships with Sylvie Russo and Joan Baez. The story, based on the book Dylan Goes Electric (2016) by Elijah Wald, culminates in Dylan’s groundbreaking and controversial electric performance at the 1965 Newport Folk Festival. 29-year-old Timothée Chalamet, who played Dylan, was stunning, but my favorite character was Boyd Holbrook’s depiction of the man in black himself, Johnny Cash, who exchanged letters with Dylan before they met at the same music festival the year before. During the movie, Baez asks Dylan “Why are you such a contrarian?” But in his letters, Cash encourages him to “…Track mud on the carpet.”

I immediately thought of Joyce Robertson, who often called me a “contrarian” and would have been livid if I tracked mud on her carpet.

I don’t recall hearing that phraseology since the last time it came out of my momma’s mouth decades ago. If she were alive today, I would apologize for being such a difficult person to rear, but I likely would not be able to change my style of addressing the world —it is, like anything, both blessing and curse.

Contrarians are world changers.

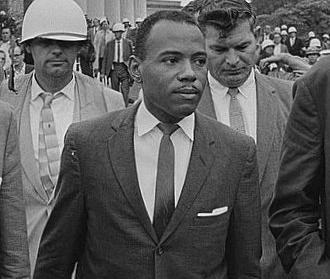

James Meredith was contrarian. Meredith, an American civil rights activist, writer, political adviser, and United States Air Force veteran who famously became, in 1962, the first African-American student admitted to racially segregated Ole Miss over the protest of Governor Ross Robert Barnett through the intervention of John F. Kennedy and the federal government. Until my post-movie research, I didn’t know Dylan wrote about Meredith in his 1963 song Oxford Town, which appeared on his second record album:

Oxford town, Oxford town

Everybody’s got their heads bowed down

Sun don’t shine above the ground

Ain’t a-goin’ down to Oxford townHe went down to Oxford town

Guns and clubs followed him down

All because his face was brown

Better get away from Oxford townOxford town around the bend

Come to the door, he couldn’t get in

All because of the color of his skin

What do you think about that, my friend?Me, my gal, and my gal’s son

We got met with a tear gas bomb

Don’t even know why we come

We’re goin’ back where we came fromOxford town in the afternoon

Dylan, Bob. The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan. Columbia Records, 1963

Everybody’s singin’ a sorrowful tune

Two men died ‘neath the Mississippi moon

Somebody better investigate soon.

I know Governor Barnett’s son, Ross, Jr. and his granddaughter, Judy, from practicing law in Jackson. My legal mentor, L.C. James, used to tell me stories about Governor Barnett, who also practiced in Jackson after he left office. In a backwards way, Barnett was a contrarian too, stubbornly holding on to old injustices, like most of Mississippi, as the world around him changed for the better.

Jesus was the ultimate contrarian. Indeed, Reverand Martin Luther King, Jr. tracked a good bit of mud on the carpet of the American South. Contrarians are catalysts for transformative change, challenging conventional thinking and pushing boundaries in ways that reshape society. By questioning accepted norms and refusing to conform to popular opinions, they provoke new ideas and alternative perspectives others overlook. History is filled with contrarians— like Jesus, MLK, Dylan, Cash, Meredith, Kennedy and even my momma, Joyce, from whom I inherited by contrarian ways.

Society needs contrarians because they challenge deeply ingrained injustices. Their willingness to think differently and act courageously inspires progress, sparks innovation, cultural revolutions, and paradigm shifts, redefining what is possible.

In a world that rewards conformity, contrarians remind us that true growth comes from embracing discomfort and disruption. As we celebrate the civil rights efforts of Martin Luther King, I challenge you to activate your unique gifts and go out into the world and track mud on the carpet.

Craig Robertson is the founder of Robertson + Easterling. For over 25 years, he has practiced exclusively high net worth divorce and complicated family law in Mississippi. He sees his role as extending beyond legal guidance to encompass the support of clients through the intricate and challenging landscape of emotions that accompany divorce –promoting health and wellness practices. He provides compassionate and empathetic assistance for those who need to track mud on the carpet.