I grew up a mile or so from Apple Ridge Shopping Center in South Jackson. Apple Ridge was the turnaround spot for teenagers who cruised McDowell Road on Friday and Saturday nights. It had a bowling alley and a grocery store and an iconic neon sign with a red apple as its highest feature, the words stacked top to bottom, and an arrow once lighted with dozens of bulbs directing motorists to its shops. Even before I was old enough to drive, I road my bike there all the time. The grocery store went through several brand names during my childhood, and it was not uncommon for me and the neighborhood kids to walk through the establishment barefooted, which would make the bottom of our feet turn black. This condition was termed “grocery store feet.” The shopping center was demolished in 2021 about this time of year.

I attended the local public high school named after Oscar H. Wingfield. My baseball coach and history teacher was Willis Steenhuis. My brother, Keith, played baseball for him too. By the time I was on his squad as a 9th grader in 1989, he was already a legend.

Coach was different.

He colored his fluffy white hair blonde, and it sometimes took on different shades depending on the color choices available to his wife, Mary, for his monthly touch up. I actually have no idea who colored Coach’s hair, but in my mind, it must have been his bride, although I had not met her until he was laid to rest in 2018 at the age of 82. Swarms of his players and coaching colleagues were there to pay their respects.

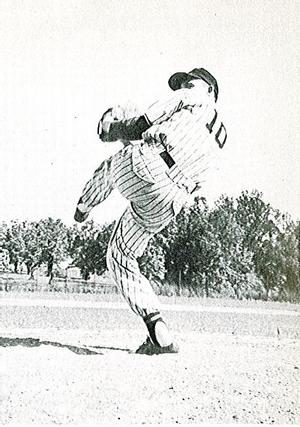

Coach was a pitcher in his playing days for Central High School (which was located in downtown Jackson), Hinds Community College and Mississippi College. At one time, he had the MC school record for most wins. He was drafted by the Baltimore Orioles, but like most ball players, he never made it to The Show. He returned to Jackson to become a Coach at his alma mater, and was mentored by men named Cooter Berry, Skin Boteler and Enis Proctor. After coaching at Central, he took the helm at Wingfield and throughout the years, he would be inducted into four Halls of Fame for his playing and coaching accomplishments.

Our team played at Leavell Woods Park, which was several miles from Apple Ridge and even further from Wingfield. The wooden fence at Leavell Woods was painted green and probably stood eight feet tall. The distance from home plate to the barrier was relatively short, especially in right field, as there was an entrance road and a park with a metal slide shaped like a rocket ship just beyond its shadow, both of which limited the available space. Because of this shorter outfield and the freakish athletic abilities of our right fielder, Andre Thompson, many batters were thrown out at first base who thought for a moment they had hit a single. Just past the left field fence was Dona Avenue, and many Wingfield Falcons hit the street (and sometimes a moving car) with homeruns –sort of like the Chicago Cubs and Waveland Avenue past the ivy at Wrigley Field.

When he was our skipper, Steenhuis was in his late 50’s, but he still tossed batting practice most days, usually with his shirt off. In fact, shirts were optional for the entire team during practice. I bet Coach threw over a hundred pitches per outing multiple times per week. It was very common for Steenhuis to stand behind a garbage can or anything else which would slow a baseball up the middle rather than an actual protective netting. Our training sessions were mostly the same. First, about ten or twelve of the guys who were starters or up-and-comers would take batting practice in groups of three or four, with the rest of the crew filling the infield and outfield to shag balls. Then, most of that first group would switch to defense in their regular positions while the rest of the team would take turns stepping to the plate for one swing at a Steenhuis pitch to put the ball in play, creating game-like situations for the starters.

Coach had an entourage made up of men who were like the cast of the Muppet Show. There was Coach Eric Lantrip, who was an art teacher with limited athletic ability, but he painted our dugout with a cool logo and tribute to the success of years past. He was always present and helpful. There was Coach Rob Berry, who was younger and more athletic. We also had some older baseball guys who lived close by, who would hang around the dugouts and walk around the outfield during practice for exercise, serving as our version of Statler and Waldorf. But for most of his life, the person who never left Coach’s side was Ronald Fisher, who everyone calls Fish. Fish has a prosthetic eye, which he would take out from time to time to freak us out. Fish also had limited athletic prowess, but he studied the local game for decades, and over time became a legend himself in ballparks around the Jackson metro area.

Coach made baseball fun. He was old-school. He traveled in a 1983 Lincoln Continental Mark VI, keeping all of our equipment in its massive trunk. He said many things daily which would have been grounds for disciplinary actions back then and would have gotten him immediately cancelled today. He taught us old baseball phrases like can of corn, chin music, around the horn, ducks on the pond, bush league and southpaw. He gave us handwritten stat sheets multiple times each season. When he was excited about anything, he would exclaim, “Hey Racky Kacky!” I have no idea what it means, but I can hear him say it in my mind if I close my eyes. It must have been something he heard his grandfather or a coach say. I asked an old friend and teammate if he knew its meaning, and his response was “…it is simply the most unique and original expression of excitement I have ever heard in my lifetime.”

I agree.

Coach wanted us to be heroes in our high school. On big gamedays, he would participate in the morning announcements over the school intercom, encouraging our classmates to attend the contests with the rally cry of “All the Way to State!” He would also choose a Player of the Week, and post statistics and newspaper articles to a bulletin board in the main hall of the school.

He made us feel like we were important.

Coach was a competitor. During a game one year, the fans of an opposing team were heckling him about the color of his hair. Coach did not say anything, he simply stopped in front of the visiting team’s bleachers on his way back to our dugout from coaching third base and threw the crooked middle finger of his right hand into the air. As he turned back toward the direction he was headed, he put his head down, keeping his arm and finger raised.

And the legend grew.

When we traveled to out-of-town games, the Jackson Public School District would pay for us to go to McDonald’s. We even got an apple pie. During the playoffs, the quality of the dining establishment was upgraded to Western Sizzlin’, and instead of the typical “yellow dog” school bus, our carriage was an actual touring bus from a local travel company. It was as if we were professionals.

There are hundreds of men who were impacted by the life of Willis Johnson Steenhuis. He was truly one of the unique characters of the great tradition of baseball in Mississippi. Although I never won a state championship playing for Coach, under his watch I learned how to be a competitor and a teammate. It has served me well in life. I always call a lazy pop fly a can of corn, and in the right setting during a moment of excitement or transcendence, the seemingly made-up and mystical phrase “Hey Racky Kacky” may be whispered under my breath through a little smile.

Craig Robertson is the founder of Robertson + Easterling. For over 24 years, he has practiced exclusively high net worth divorce and complicated family law in Mississippi. You will want him in your corner because he knows the things you care about deeply are at stake, and he will counsel you about wholistic modalities to foster health and wellbeing. He was a four-year letterman for Coach Willis Johnson Steenhuis of the O.H. Wingfield Falcons.

Special thanks to my friend and teammate, Marc Rolph, who edited this article and helped me reminiscence about Coach.