Rachel and I love New Orleans, mostly because we share a passion for its world-class cuisine. We were engaged to be married there on August 25, 2001. It was a Saturday. We had planned to spend the day in the city, but I had no preconceived agenda. This was before couples hired photographers to capture the moment for social media, or hosted parties to involve friends and family. As a veteran divorce lawyer, I have thoughts on that but I will save them for another day.

Someone told me about Audubon Park, where the zoo is located. There is a catchy song about the Audubon Zoo. You have probably heard it at a jazz brunch. Here are a few of my favorite lines:

I went on down to the Audubon Zoo

And they all asked for you

They all asked for youWell, they even inquired about you

I went on down to the Audubon Zoo

And they all asked for youThe monkeys asked

The tigers asked

And the elephant asked me too

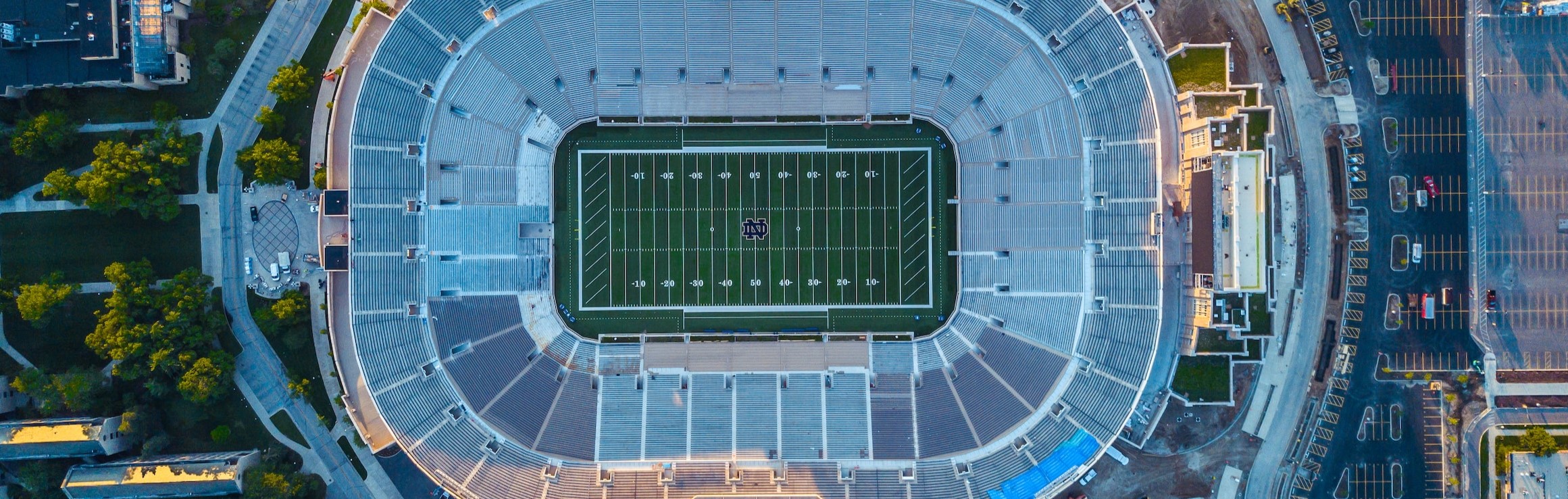

Our engagement was before widely available GPS, so I found a map, and working together, we navigated our way to the park. Audubon Park is off Saint Charles Avenue in the area of the city called Uptown. It is across the street from Tulane University, which is next door to another institute of higher learning, Loyola. In front of Marquette Hall at Loyola, there is a statue of Jesus with his arms extended in the shape of a “V.” Loyola doesn’t have a football team, so the South panel mosaic in South Bend is much more well known.

I parked my car on Saint Charles, and down the way, I spotted a fountain I later learned was named after the Gumble family, who like Touchdown Jesus, were Jewish. The fountain was erected in 1919 and features a marvelous bronze statue expressing the union of air and water. It was August in NOLA, but it was not a particularly hot morning. At the time, I was interested in photography, so Rachel did not suspect anything when I carried my camera bag, where I stashed the goods. We stopped at one of the many metal benches surrounding the fountain, and I asked Rachel to look in my camera bag for a canister of film, where she located her engagement ring.

She said “Yes”, and the rest is still being written.

Of course, August in the South marks the beginning of football season. Notre Dame opens their season with Navy. Loyola will not be taking the field. Most of the locals will be paying attention to Mississippi State, Ole Miss, Alabama or LSU.

I started playing football in the fourth grade. We practiced in the outfield of one of the bigger baseball fields at Sykes Park, which was another South Jackson youth facility where I spent lots of time, mostly playing the game for which my first testing ground was designed. Later, practices were moved to a small pitch near my elementary school playground. There was not much grass, fire ant mounds everywhere, and so many rocks. I distinctly remember the horror of Mrs. Ida May Bolian, my fifth-grade teacher, due to the bruises and ant bites all over our bodies. I feel certain she gave our Coach a piece of her mind.

Football practice was not fun. As I sit and type these thoughts to you, I am not exactly sure why I played. I was into sports, and in the early 80’s, if you played one game at school, you basically played them all. To add to the misery, our Coach was abusive. He would scream at us, embarrass us, degrade us, and make us do inhuman things like bear crawls. We practiced rain or shine, right after school, in the sweltering heat common in Mississippi’s late summer and early fall afternoons.

One drill I particularly disliked was called bull in the ring. It elated our ruthless Coach. An unlucky elementary school student-athlete would be handed a football and forced to the middle of a circle formed by his teammates. Coach would call the jersey number of one of the boys on the outside of the circle, and the player with the football would need to quickly identify the teammate whose number was called, and then attempt to run over him to remove himself from the circle. That, in and of itself, may have had football merit, but while Coach would only call out one jersey number for some of his favored “bulls”, for mouthy kids like me, I may contend with multiple head-hunting teammates from lots of different directions. The torture we withstood made us a hardened bunch, and we destroyed our competition each week —never even coming close to losing a game. Did I mention I went to a Christian school?

Touchdown Jesus.

After football season was over, basketball began. The same guys played. Hoops suited me a little better, because I was tall although quite lanky. Unfortunately, we had the same Coach. One day I was not where I was supposed to be, and Coach threw a basketball from half court, striking me in the head and knocking me to the floor. While I was not physically injured, I was utterly humiliated. My teammates looked on in horror and shock with the knowledge that they could be next. This and other events helped nurture my solid distrust for authority.

I eventually left the Christian school for the Jackson Public School District in ninth grade. Coach left around the same time. Unbeknownst to me, he ended up coaching football at one of our rival JPS opponents. I shook his hand after our game that year, which was the last time I would see him on a football field.

I played football all the way through high school, but I focused most of my energy and attention on baseball. I had many positive experiences with Coaches and with sports in general. I have written about Willis Steenhuis and Ron Polk in the past. Of course, after competitive sports was over, I met L.C. James and became a divorce lawyer.

In late 2004 after I had been a domestic relations lawyer for only a few years, I got a somewhat cryptic email message asking for help. It was signed “Coach.” By that point in my life, I had been in relationships with an abundance of coaches, so I did not immediately know who was trying to contact me. I would eventually learn it was the bear-crawl-loving, bull-in-the-ring-organizing, basketball thrower from elementary school, and he was in bad shape.

Coach suffered an automobile accident the same year I graduated high school and it crushed his body. Four surgeries later, he was 100% disabled. He and his family could not afford to live on his wife’s small salary and his disability checks alone, so Coach worked three jobs including one as a night shift security guard. On top of his prescribed pain medication, Coach would take handfuls of “trucker pills” to stay awake for his all-night job. By the time he got home, he was so wired he could not sleep, so he drank cheap beer until he passed out.

He had lived this way for years.

By the time Coach reached out to me for help, he and his wife had been separated for quite a while, and he did not own a car. He was living in the office of his friend’s used car lot with his Pomeranian named “Boo.” He would drive whatever car was on the lot to get around, and his kids would hardly speak to him. Not only was he staring down the barrel of divorce, he had multiple run-ins with law enforcement, and his wife had obtained a temporary restraining order, which, in hindsight, she certainly needed.

After months of legal maneuvering, we tried Coach’s divorce in front of Judge John Grant, III, who was one of my favorites. In a reversal of roles, it was Coach who had the ball as the bull in the ring, fighting for the scraps of his life, longing for an opportunity to be in a relationship with his children.

It was bigger than football.

Working against a notoriously aggressive counsel opposite, I fought as hard as I could for Coach. In my closing argument, which is rare in a Mississippi divorce trial, I had my hands on Coach’s shoulders, begging for equity for this complicated man. Understanding Coach was broken, and having a glimpse of his home life, I felt deep compassion for him. The experience of being his advocate was healing for me. I genuinely believe Coach simply demanded from us what he expected from himself —everything. Although I am certain he traumatized his family like he traumatized me on the football field, as Judge Grant pointed out in his oral finding of fact, there was a lot of good inside of my Coach, and like everyone, he deserved an opportunity to start over. Without condoning his bad acts and after ensuring his family would be okay with their limited resources, Judge Grant had mercy on Coach.

Touchdown Jesus.

It has been 22 years since that day in Audubon Park next to the fountain, and 16 since I tried Coach’s divorce. I have come to learn that our Arms-Raised-Savior grants us perspective over past events, and not all suffering is bad. Coach taught me to give everything I have for a given endeavor, and I bear crawled my way into an understanding of how to overcome failure and embarrassment. I do not think I have seen Coach since we wrapped up his legal mess, but if somehow these words cross his eyes, I want him to know I am grateful for the lessons he instilled in us boys notwithstanding the objections of Mrs. Bolian. I hope he has found the ability to tame that relentless drive which was contemporaneously a blessing and a curse.

Craig Robertson is the founder of Robertson + Easterling. For over 24 years, he has practiced exclusively high net worth divorce and complicated family law in Mississippi. You will want him in your corner because he knows the things you care about deeply are at stake, and he will counsel you about wholistic modalities to foster health and wellbeing. He learned to be resilient in a circle of boys with a football in his hand, whether he knew it at the time or not.